Travel: the Ultimate Complex Adaptive System

Why the travel industry might just be the Ultimate Complex Adaptive System. How complexity science, non-zero-sum thinking, and the insights of Arthur, West, Sleep, and NZS Capital reveal the hidden networks at play.

STRATEGYINVESTINGCOMPLEXITY

komorebi

7 min read

The Oldest Network on Earth

Travel is one of humanity’s oldest and most enduring industries. It has been with us since the first merchants crossed deserts for trade, pilgrims walked to holy sites, and tribes crossed continents to explore new opportunities. Yet, unlike industries with clear boundaries, travel resists neat categorisation. Its edges blur across continents, cultures, and centuries.

For the purpose of this article, I’ve defined “travel” as any asset, product, service, experience, or infrastructure that enables, supports, or is consumed by people in the course of moving from one place to another — including the destinations and experiences that make the journey worthwhile. This spans everything from an uber to a local market, to a flight across oceans, to a digital booking platform; from the roads, ports, and runways that make movement possible, to the hotel, Airbnb, theme park, or safari reserve that serves as the destination itself.

Because of this breadth, travel is not a single sector. It is a complex adaptive system—a living network of interdependent parts, shaped by economics, technology, politics, and human behaviour. Like all complex systems, it evolves continuously, often in ways no single actor can predict or control.

Compounding in a Complex World

The antifragility we see in travel isn’t a quirk of the industry—it’s the same structural resilience you find in other complex adaptive systems. Complexity science has been applied across domains: riots and political outbreaks in social systems, bubbles and crashes in economic systems, predator–prey dynamics in ecological systems, immune responses in biology, and learning feedback loops in artificial intelligence. Each system runs on interconnected agents, feedback loops, and nonlinearity—meaning a small spark can cascade into a full-blown transformation.

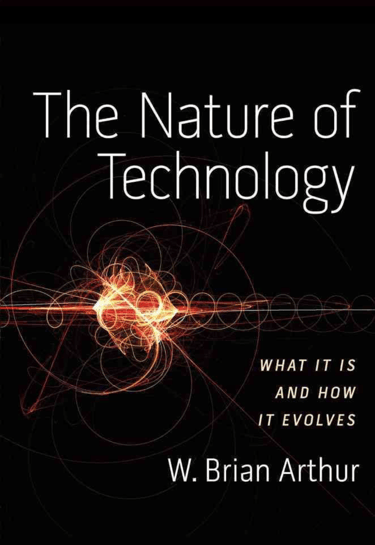

Two thinkers from the Santa Fe Institute have shaped my own lens on this. W. Brian Arthur’s work on increasing returns and the nature of technology explains why certain technologies pull away from the pack. Once a platform builds early advantage—through network effects, data feedback loops, and user lock-in—it can enter a self-reinforcing orbit. You can see it in tech (Google, Amazon) and in travel (Booking.com’s hotel distribution dominance, Airbnb’s grip on alternative accommodation). Once the flywheel spins, it’s not just hard to catch—it’s hard to even see from the starting line.

The Travel Network: Antifragile by Design

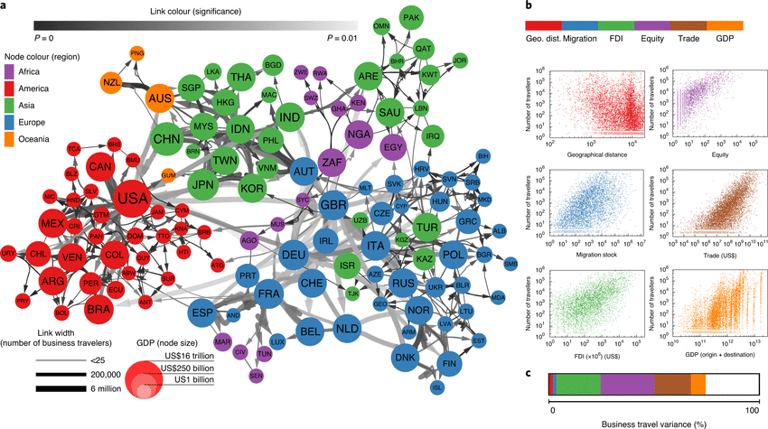

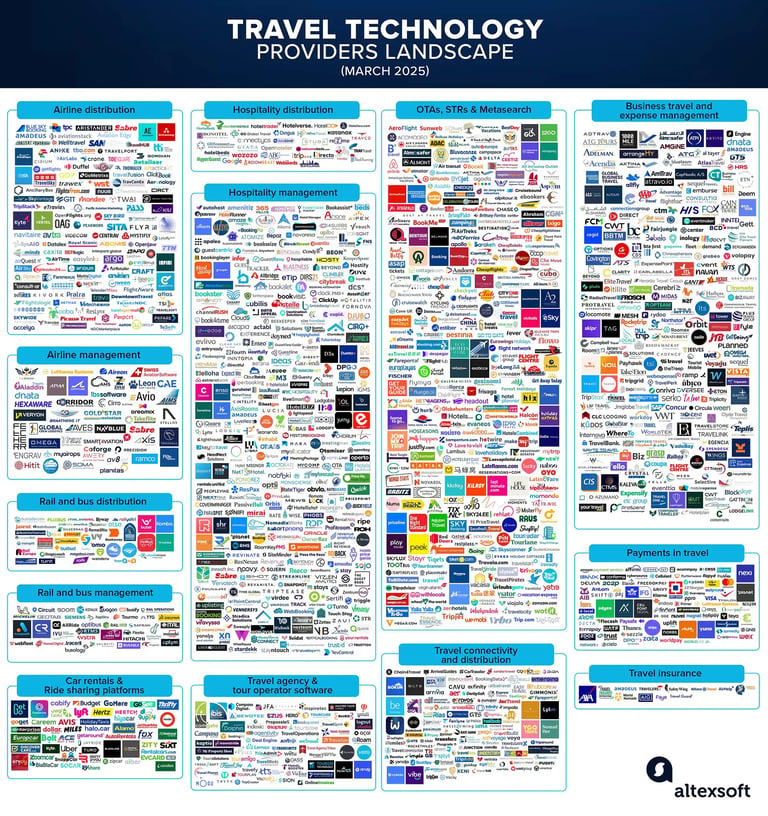

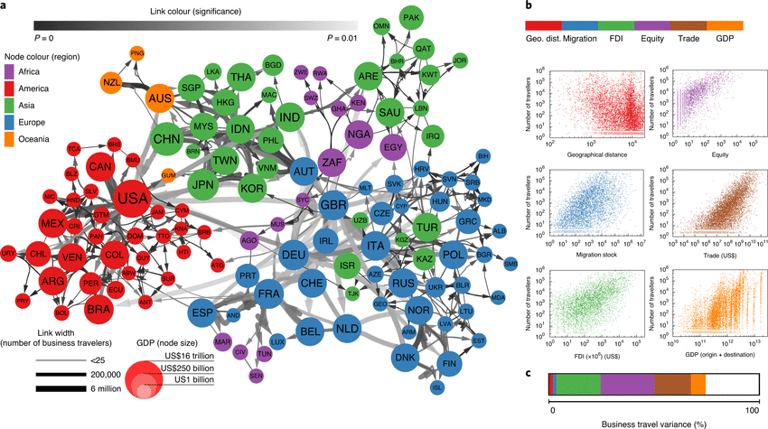

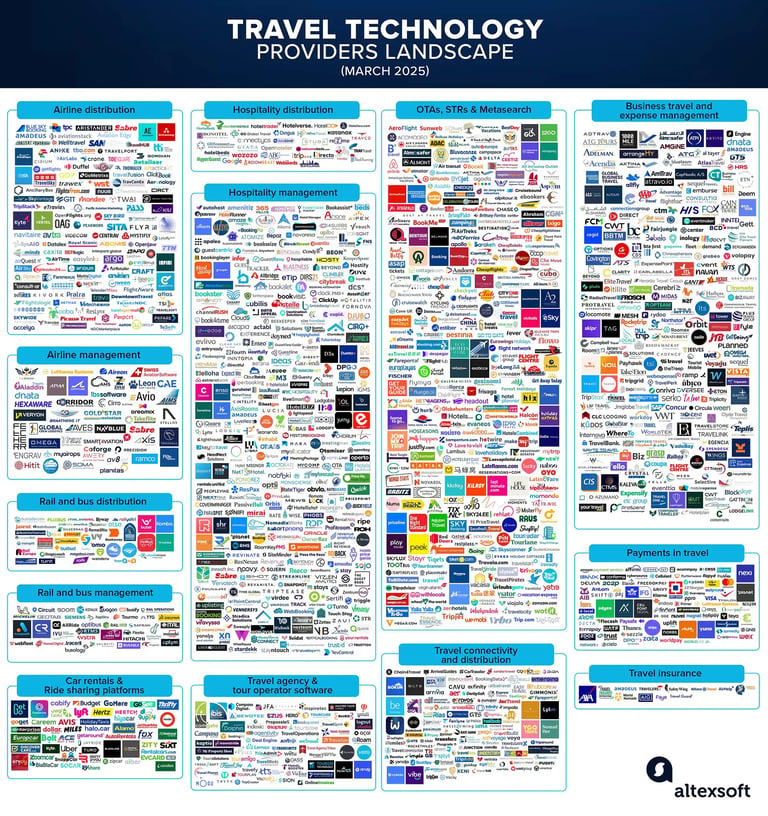

Look at the travel technology landscape map and you see hundreds of logos—booking platforms, airline systems, hospitality management tools, expense software, payment providers. It looks chaotic, but it’s really a living organism. Each company is a node; each integration, partnership, and transaction is a synapse firing. Change one node—say, raise OTA commission rates—and the ripple alters distribution costs for thousands of hotels and flight operators. Having built and scaled hospitality businesses, I’ve seen how a single vendor outage or policy shift can derail a season.

Now zoom out to the world air transport network map. Every blue dot is an airport; every green line is a route. This is the circulatory system of the global travel economy. My investments—in PDD, Occidental, Brookfield, Wise, and operators in hospitality and marine manufacturing—have taught me that resilience here isn’t just about keeping planes flying. It’s about anticipating how disruptions in one artery—a volcanic eruption, geopolitical flashpoint, or airline bankruptcy—can clot traffic, reroute demand, and re-price entire destinations overnight.

Then came the system’s most revealing stress test in modern history: COVID-19. Within weeks, the network you see on these maps collapsed. Airports went silent, airlines parked fleets in the desert, hotels shuttered, and tourism economies flatlined. Yet instead of disappearing, the system adapted and—critically—some participants emerged stronger. Marriott leveraged its loyalty ecosystem to maintain customer engagement and accelerate recovery. Booking and Airbnb pivoted to flexible, local, and long-term stays, gaining share as travel resumed. Even luxury tour operators like Ker & Downey Africa, where I once sat in the operator’s chair, found ways to thrive by doubling down on high-value, low-volume travel, building deeper client relationships and expanding their footprint while competitors faltered.

This resilience is not new—it’s embedded in travel’s DNA. Japan’s oldest hotel, Nishiyama Onsen Keiunkan, has been passed down through 53 generations since 705 AD. Another, Hōshi Ryokan, has operated continuously since 718. These aren’t just curiosities; they are proof that hospitality can survive wars, famines, pandemics, political upheaval, and technological revolutions. The same antifragile traits that carried these inns through 1,300 years—deep cultural roots, adaptability, and a service model that renews itself with each generation—are the same traits that allowed modern giants to navigate COVID and emerge stronger.

Biological systems work this way: forests regenerate after fires, coral reefs adapt after bleaching, and species evolve under pressure. Travel, a millennia-old system, carries the same regenerative logic. It has redundancy baked in—multiple modes of transport, diverse market segments, and operators across every price point and geography. COVID didn’t make travel uninvestable; it proved that the entire global travel economy could stop overnight, shed obsolete layers, evolve in real time, and come back fitter. For investors, that is not a weakness—it’s the ultimate moat.

What is a Complex Adaptive System?

Bill Gurley first introduced me to the concept of Complexity on a podcast, referencing W. Brian Arthur’s work on increasing returns and lock-in. He praised the Santa Fe Institute’s research on complex adaptive systems and recommended Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos by M. Mitchell Waldrop.

That 60-minute conversation did what 20 years of formal education never quite managed: it made me rethink how the world actually works. It rewired my investment philosophy and, frankly, my long-term business thinking.

Complex adaptive systems are made of many interacting parts—or “agents”—whose collective behaviour can’t be predicted by studying the parts alone. They’re complex because the interactions are endless and unpredictable. They’re adaptive because the agents respond to feedback from the environment, changing their behaviour over time. And they’re nonlinear, which is short-hand for “tiny things sometimes blow up into very big things”.

In Yellowstone, reintroducing wolves set off a chain reaction: deer changed grazing patterns, forests regenerated, beavers returned, and rivers shifted course. All because a few grey predators started showing up for dinner again.

Travel works exactly the same way—just with fewer wolves and more airport lounges. It’s a sprawling network of infrastructure, operators, platforms, regulators, and travellers, all influencing each other in ways no single person—or even a self-proclaimed “visionary” CEO—can fully control. One volcanic eruption in Iceland and suddenly flights are grounded, hotel bookings collapse, rental cars run out, and Icelandic fish miss their sushi appointments in Tokyo.

Feedback loops are everywhere: a destination goes viral on Instagram, airline routes follow, hotel investors pile in, prices spike, and eventually travellers chase the next shiny location. By the time the brochures are printed, the network has already morphed.

The travel industry isn’t a neat vertical; it’s a complex adaptive system in perpetual motion. If you want to operate or invest in it successfully, you’d better respect its unpredictability—because unlike a spreadsheet, it doesn’t care about your assumptions.

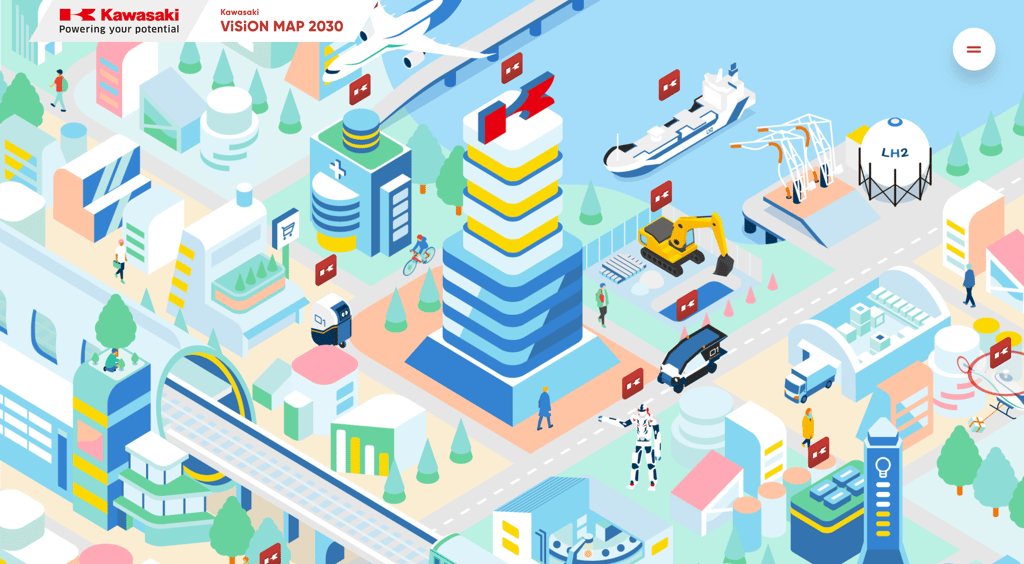

Kawasaki’s 2030 vision hints at what travel looks like when every node — from ports to autonomous vehicles — are part of the same living, adaptive system.

Hōshi Ryokan in Japan has welcomed travellers for over 1,300 years — a living reminder that the most resilient travel companies aren’t just built on infrastructure, but on trust, tradition, and the quiet compounding of human connection.

Brian Arthur’s The Nature of Technology makes the connection to resilience explicit: technologies evolve by recombining existing components, and the most adaptable organisations are those that can reconfigure their building blocks quickly when conditions change. This recombinatory capacity is the bridge between technological evolution and organisational adaptability—the same logic that allowed travel’s winners to pivot during COVID.

Geoffrey West’s work on Scale adds another layer: size brings efficiencies, but survival comes from stacking new S-curves. Without innovation, growth slows, entropy wins, and even the giants stall. Some inputs (like infrastructure) scale efficiently, others (like innovation or talent density) scale superlinearly—meaning they get disproportionately stronger with size. But negative side-effects—crime, bureaucracy, or in corporate terms, inertia—also grow faster than you think. The lesson: growth buys time, but innovation buys survival.

This complexity lens is where two modern investment influences—Nick Sleep and NZS Capital—fit perfectly. Nick Sleep was early in understanding that the most enduring businesses are destination businesses: companies so integral to customers’ lives that traffic flows to them without ongoing persuasion. His writing on the robustness ratio and non-zero-sum business models showed that long-term compounding depends on creating value for all stakeholders, not just shareholders.

NZS Capital take this further, building an investment philosophy grounded in adaptability, resilience, and positive-sum outcomes. Their work reframes portfolio construction for complex systems: in ecosystems like travel, semiconductors, or streaming media, the most robust participants aren’t the ones extracting the most—they’re the ones enabling others to thrive alongside them. In the semiconductor industry, for instance, extreme specialisation has created a network of interdependent companies with above-average margins across the chain—an elegant non-zero-sum equilibrium. In travel, this might look like an airline–hotel–local operator partnership that grows the market instead of fighting for static share.

This perspective has rewired my own investment approach. I now look for travel and travel-adjacent businesses that have the DNA of a keystone species—slow-growth resilience in fragmented markets, digital assets that scale with zero marginal cost, the potential for increasing returns, and the ability to spawn new business lines without losing their core. The best of them create positive-sum outcomes for their entire ecosystem, reinforcing their position every time the network adapts.

In other words, I’m not just looking for companies that can survive the next COVID. I’m looking for the ones that emerge from it stronger—just like a Japanese ryokan that has outlasted wars, famines, and revolutions by constantly renewing itself while never losing sight of its purpose. Complexity science doesn’t just explain why they survive—it explains why, for the long-term investor, these are the businesses worth owning.

For a deeper dive into how these principles apply to building resilience and adaptability in the face of uncertainty, see my article Rethinking Risk, Resilience, and Adaptation in a Changing World.

Copyright Komorebi Investments Pty Ltd 2025

Explore:

Building the future of travel, mobility, and infrastructure.